The Changelog-Versioning Revolution

At Batteries911, the BE team has the responsibility of maintaining an API that is consumed by 3 (soon 4) different clients: two iOS applications and a SPA. This means that, whenever we introduce a change, we need to be absolutely sure that the change is either non-disruptive or, if it is, that it was communicated properly and coordinated with all the FE teams.

For a long time, we just relied on Slack for this job: whenever we changed something in the API, we’d send a message in a Slack channel aptly named dev-integration, so that everyone knew about the change (or so we thought).

We were pretty satisfied with our approach, but then things started to break because people were not aware of some change we applied or some endpoint we removed. Going back to fix the issue when the release had already reached the QA phase was time and money-consuming. Moreover, we were losing visibility of how the API was changing over time, which meant it was often hard to track down issues.

Much to the joy of the iOS and Web teams, the decision was made to adopt Semantic Versioning for our API and to start keeping a changelog.

There were definitely challenges involved in this, though: how were we supposed to ensure that the changelog was accurate? Who would take on the responsibility of writing changelog entries at the end of each release? We already had so much on our minds that the additional burden of keeping a detailed list of every single change seemed like an impossible feat.

Also, no one was happy with the fact that we had just lost our rolling release approach to releasing and would start to version our software like some old, boring enterprise.

In other words, there was definitely some initial resistance.

And yet, we came to love our changelog and our version numbers, and the structure and guidance they provide. Today, we keep our changelog entries diligently, and we tag our major, minor and patch versions with care.

So how did we do it?

(Not) Everything Needs a Version Number

Let me start with an important point: not all software needs versioning, or a changelog. If you’re building an MVP, versioning is probably not for you. If you work on a traditional full-stack website, then it’s very likely you don’t need versioning either.

The bottom line is that versioning is an overhead on top of your development process, so it should only be adopted where it provides tangible benefits. With that said, there are many many cases where it provides benefits, so think twice before you dismiss it as useless. Here are some examples:

- Open source software: pretty much all serious open source projects adopt versioning and a changelog of some kind. In fact, this is one of the things I look for in a project to determine whether it’s well-maintained. Users need to know which APIs you change and they need the assurance that you’re not going to break their implementation at a whim’s notice, so versioning here is non-negotiable.

- Private and public APIs: whether you’re building a private (as is the case with B911) or public API, the teams leveraging your software will want to be informed of what changed and how, so that they can update their implementation accordingly. A good versioning practice and a detailed changelog will go a long way towards securing your success as a team and reducing — if not eliminating — “But I thought…” remarks.

- Enterprise software: enterprise clients want to have complete oversight of the development process — versioning is one of the tools that can be employed to achieve this. It provides transparency and — when used properly — greater stability.

- Established SaaS products: lately, I see more and more SaaS companies presenting a changelog to their users. These are a bit different from the changelogs you are used to seeing on GitHub — they are usually in the form of a blog post, newsletter or Headway widget. This is a nice way to keep your customers engaged and informed. It also lets them know that you care about them and are always working on things they love, so it’s worth to give it a try.

Even if you don’t belong to any of these categories, you might still want to practice your versioning skills, which is perfectly fine. Just be mindful of the additional work you’ll have to do, and make sure that you’re not bogging down your team with unnecessary chores.

An Effortless Versioning Process

The versioning process that we came up with is dead-simple. The trick was to make sure that it was impossible not to follow the process, so that people were forced to adopt it and it became part of their workflow. For instance, here’s what we did at Batteries911 for the initial setup:

- We adopted Semantic Versioning: we assigned an initial version number to the current state of the codebase. Since we had already started, this was arbitrary (0.3.0) and reflected the perceived state of the product. If you are starting a project from scratch, you might want to just start with 0.1.0. Remember that the rules are different before 1.0.0: minor releases (0.X.0) can contain breaking changes, as it is expected that you will take some time to define an ideal API.

- We created a changelog: we used Keep a Changelog as a format. We created a first entry for our current version and started from there.

- We set up a PR template: GitHub has this nice thing called pull request templates, which are Markdown files that will be used to prefill the description field of new PRs. To make sure that people wouldn’t forget to record their PR in the changelog, our template contains a checklist. In order for the PR to be merge-able, all tasks in the checklist must be completed. Example tasks are “I have updated the tests”, “I have updated the API docs” and, of course “I have created a changelog entry.”

- We exposed the version number. One cool trick that we did was setting the current version number in a constant in our config/application.rb and including it in the HTTP headers of every response. This way, clients can ensure that they are using the correct API version (in case you maintain multiple versions at once, or want to raise an alert when a client should be updated, because it only supports an older API version).

With this setup in place, it was pretty much impossible to miss a step of the process: it would be caught either by the checklist or by the PR’s reviewer. Of course, this approach requires discipline: all changes must be made in a PR and all PRs must be reviewed thoroughly. If you can ensure this happens, you’ll have peace of mind.

The Changelog-Versioning Relationship

At this point, you might be wondering why I speak of versioning and the practice of keeping a changelog seem as if they were so intertwined. After all, you can record changes even without version numbers, and you can have version numbers without recording changes, right?

Well, since Semantic Versioning requires you to advance version numbers not based on some arbitrary choice, but on the kind of changes that you are introducing with the new version, a changelog is an invaluable tool when picking the new version number.

For us, a new release usually starts without a defined version number. We just call it “unreleased”, because don’t know what kind of changes we’re going to make — we do have an idea because we know what goals we want to achieve, of course, but we might not always know how to do it yet. Then, as we start writing code, we also start accumulating entries in the release’s changelog.

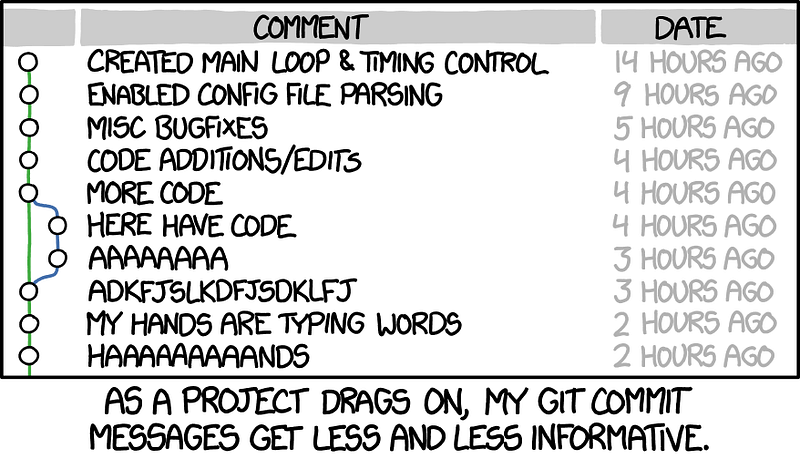

Source: xkcd.com

When the time comes to release the new version, the team lead looks at the changelog and can immediately see what number to increment: if the release only contains bugfixes, we need to increment the patch number; if the release contains new features, we need to increment the minor version; if the release contains backwards-incompatible changes, we need to increment the major version (hint: if this happens too often, something’s off).

This approach works perfectly for us, because it allows us to keep track of everything that happens without sacrificing the smallest hint of flexibility.

We are currently experimenting with novel ways and processes that will keep us in check: for instance, we are working on a GitHub bot that will analyze PRs to check for changelog entries and whether those entries seem to make sense. This can be achieved with some API introspection and is proving a very fun challenge to work on.

For the time being, we are quite happy with a process that satisfies everyone: the BE team has more visibility into what they are doing and their work is more structured, the FE teams are always in the loop about what’s going on with the API, and management can easily get insight into the product’s development and velocity.

tl;dr

- Keep a changelog. Even though you think it’s not for you, it probably is.

- Establish a process that eliminates human error.

- Keeping changelogs and tracking versions are intertwined: the former helps the latter immensely.

- Changelogs are cool.